IN FOCUS: With 'no place to retreat to', Singapore advances to protect its coastlines

The planned "Long Island" reclamation project is the latest weapon in the low-lying nation's arsenal, as it braces for the potentially devastating impact of rising sea levels.

What Singapore's East Coast could face without coastal protection measures in place. (Animation: CNA/Rafa Estrada)

This audio is AI-generated.

- Long Island marks one of Singapore's first long-term, coastline-specific measures since it began studying its shorelines

- These longer-running studies are complemented by short-term "no regret" initiatives such as building sea walls

- Singapore also prioritises environmental sensitivity and "multifunctionality" - as seen with Marina Barrage, which serves as a flood control dam, water source and iconic feature at the same time

SINGAPORE: As efforts to tackle rising sea levels go, Singapore has unveiled one of its most eye-catching ones yet.

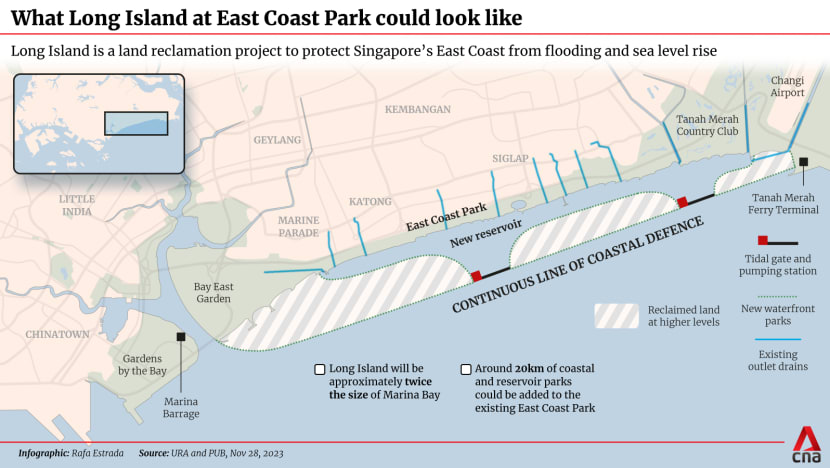

It intends to construct a new island out of reclaimed land, off its east coast where a recreational park - the country's largest - lies less than 5m above mean sea level.

Dubbed "Long Island" for now, the 800ha, decades-long project is expected to host a reservoir and more recreational and residential spaces.

When Long Island comes to fruition remains to be seen, but the sheer magnitude of the endeavour points to how Singapore is attempting to address some of its biggest challenges at once, experts say.

"At the same time as creating a huge amount of much-needed new land, you're also going to create a new reservoir and you're going to meet the fundamental challenge of protecting the lowest part of Singapore," said professor of coastal science Adam Switzer from the Nanyang Technological University's (NTU) Asian School of the Environment.

"It will be hard to find something that rivals the scale (of Long Island) ... this is going to go from the Marina area right across to near Changi Airport. That's quite a significant distance."

Long Island also marks one of the first long-term, coastline-specific measures to be rolled out since Singapore began, in 2021, progressive studies of its different shores.

The study of the city-East Coast stretch - where Long Island will be located off - took precedence due to the critical infrastructure it holds, including Changi Airport, the central business district and other areas key to the economy.

Singapore's strategies for adapting to sea level rise will also be showcased at only its second-ever Pavilion at the 2023 United Nations climate change talks or COP28 in Dubai, which started on Thursday (Nov 30) and will run to Dec 12.

CNA takes a look at these existing measures and other possible initiatives which Singaporeans may soon spy along their shorelines.

SURVIVAL AT STAKE

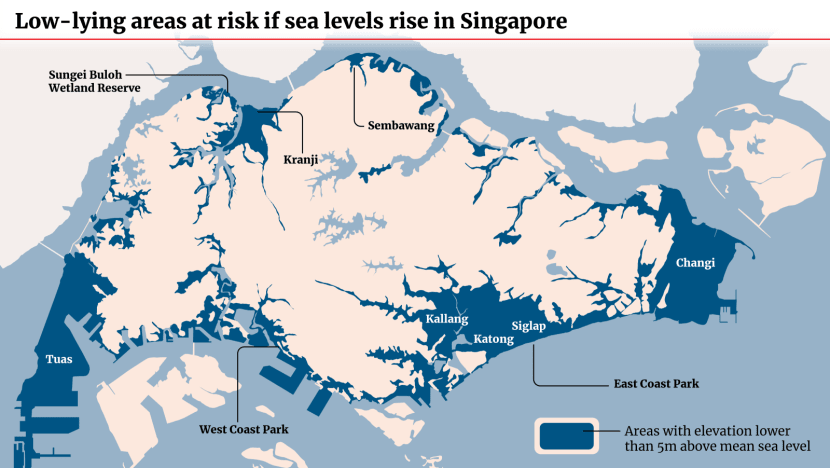

As a low-lying nation with 30 per cent of its land less than 5m above mean sea level, Singapore may lose important swathes of land even if sea levels only rise by 1m by 2100, as projected in studies.

Events such as high tides and storm surges - creating an abnormal rise of water - may cause mean sea levels to spike by 4m or 5m instead, experts say.

According to Singapore's national water agency PUB, mean sea levels are increasing at a rate of 3mm to 4mm per year.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong acknowledged the challenge at his 2019 National Day Rally, noting it would take S$100 billion or more, spread over 100 years, to fight rising sea levels. The next year, Singapore injected S$5 billion into a new coastal and flood protection fund.

"For a small island state with no place to retreat to, the survivability of Singapore is at stake which we cannot even tag a cost to," said Professor Koh Chan Ghee from the National University of Singapore's (NUS) College of Design and Engineering.

Singapore's East Coast precinct - one of its lowest-lying areas - has already seen flooding in past years due to heavy rainfall and high tides. "If nothing is done to protect the East Coast from sea level rise, it will be inundated permanently resulting in loss of use of space and livelihoods," said civil engineering professor Yong Kwet Yew from NUS.

NTU's Earth Observatory of Singapore research assistant professor Stephen Chua said that while a 1m rise was a good gauge for engineering solutions, sea levels around Singapore could potentially rise by 20 per cent to 30 per cent above the global average, due to the country's location.

"That's because of the dynamic interaction between ice sheets and the land and the way water behaves around the world. Sea level is not level," he said.

"Because of that Singapore's (sea levels) may, under very 'high-end' scenarios ... go up to potentially 1.2m. But again, there is a range of uncertainty from 0.4m to 1.2m."

SURROUND SINGAPORE WITH WALLS?

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for Singapore's 300km-long coastlines with their different typologies, said Prof Yong from NUS.

"New, integrated solutions are site-specific and tailored to complement varied land uses in that area," he added.

Long Island, for example, will combine land, waterfront housing and leisure amenities with coastal defence, noted Prof Yong, who also chairs PUB's coastal protection expert panel.

But varied as they are, the same principles apply to Singapore's plans to tackle rising sea levels, said Ms Sarah Hiong, a deputy director at PUB's coastal protection department.

"We have to be environmentally sensitive. We will engage our stakeholders to get inputs on some of these measures. We want it to be multifunctional as far as possible," she said.

One project exemplifying these principles is the Marina Barrage dam, which took 20 years from inception to actualisation and cost S$226 million. While its primary function is flood control, it has since become an iconic feature in the Marina Bay skyline, attracting more than 16 million visitors since its opening in 2008. The Marina Reservoir also serves as a source of drinking water and adds to Singapore's water supply.

Currently, around 70 per cent of Singapore's coastline is protected by sea walls and stone embankments. These are hard, man-made structures that protect land and infrastructure from erosion and seawater intrusion.

Other structures such as dykes, dams and tidal gates protect parts of the coastline where there are coastal reservoirs, such as along the Northwest Coast.

Why not simply surround Singapore with more strong barriers then?

Building only sea walls around the country would protect the land but also end up harming existing marine ecosystems, said the Singapore Management University's (SMU) associate professor of urban climate Winston Chow.

"The wave energy is reflected out into the sea," he explained.

Given Singapore's push towards being a "city in nature", putting it within walls would also be less than ideal.

"Visually speaking, if you have sea walls everywhere ... let's say around East Coast Park, West Coast Park ... it is at odds with the prevailing ecological aspects or functions that these parks have," said Assoc Prof Chow, who teaches SMU's Master of Sustainability programme.

"There's a disconnect which will happen if you decide to ring Singapore around with just sea walls."

Singapore is also adopting ideas from the Netherlands, a country one-third below sea level that has successfully designed systems to keep waters at bay.

For instance, PUB is studying the feasibility of storm surge barriers for a channel of water between mainland Singapore and Jurong Island. These barriers can be closed during extreme sea level events, but otherwise left open for ships to pass through. If employed, these massive structures can protect parts of the Southwest Coast and Jurong Island.

Singapore may also consider the use of polders on the mainland, following its first project at Pulau Tekong which is on track to finish by end-2024. Polders are tracts of land that lie below sea level and are reclaimed through dykes, drainage canals and pumping stations.

As a further protection, new buildings can also, simply, be constructed at a higher level. That's what Singapore is doing for Changi Airport's upcoming Terminal 5, which is being built on a site 5.5m above mean sea level and with an extensive drainage network to minimise flooding.

Long Island, too, will be reclaimed at a higher level, though authorities have yet to settle on a figure. In 2011, Singapore raised its minimum land reclamation level from 3m to 4m in view of long-term sea level rise.

Singapore has also injected a substantial S$125 million into a research programme and opened a new Coastal Protection and Flood Resilience Institute to consolidate expertise.

The launch of the centre signifies the importance of innovative solutions designed for the local context, said Singapore Institute of Technology's (SIT) engineering associate professor Tay Zhi Yung.

It also implies a need for more engineers and experts skilled in coastal protection and flood management, he added.

To come up with solutions, PUB has already been working on a model to simulate both inland and coastal flood risks, enabling it to better assess the impact of climate change on Singapore.

ADDING NATURE TO THE MAN-MADE

Going forward, experts point to "greening" structures - including transplanting organisms onto sea walls - as one possible panacea.

Dr Stephen Summers, a senior research fellow from the Singapore Centre for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering (SCELSE), is one scientist looking at how to increase ecological function and diversity on barren sea walls.

"A lot of the particle filtration is lost if there's no organisms, no filter feeders, no sponges. They take all the particles out of the water," he explained.

Without filter feeders to help purify water during seasons of heavy rain, there will be a build-up of particulates and nutrients that can form harmful algae blooms. This will in turn threaten the health of aquatic life and even humans, if consumed.

Dr Summers' centre is working on a greening method which manipulates biofilm - a slimy layer of microorganisms - on a sea wall to make it conducive and encourage other organisms to settle and colonise.

This would roughen up the sea wall and also serve to attenuate the force of waves.

POWERING UP "COASTAL SUPERHEROES"

Apart from man-made structures, Singapore's coastline comprises mostly pockets of nature such as parks or mangroves.

Mangroves, along with sea grass and coral, are natural defences that slow the flow of water before it reaches the coastline and encroaches on land.

Mangroves are currently found in areas like Kranji Coastal Nature Park.

"These coastal superheroes, with their intricate root systems and natural barrier protections, can be a valuable asset in sustaining our coastal regions," said Dr Summers.

In areas where there are no mangroves and access to land is critical, Singapore has employed geobags on shores - large sand-filled bags that reduce erosion from waves but still maintain the profile of beaches.

Yet Singapore is already showing signs of coastal erosion, said NTU's Dr Chua, who started researching the Sungei Buloh wetlands 20 years ago, and has observed retreating mangrove fringes.

"You literally see trees falling down facing the sea. Just toppling down, they can't survive. They are not able to trap enough sediments due to erosion and low sediment supply and these mangroves at the seaward edge experience dieback," he said, referring to the gradual deterioration of health in trees, in this case caused by stressful climate conditions.

The tipping point for mangroves is between 6mm to 7mm of sea level rise per year. After which, they cannot survive and must retreat landwards, according to Dr Chua, citing global data.

In Singapore, attempts by coastal mangroves to do so end up stymied by existing urban development. They get "squeezed" and die out, said Dr Chua.

Coral reefs, too, face a "precarious future", said Dr Summers.

"As the sea level rises, the coral that is fixed is not going to rise at the same rate as the rise of the sea level. It will take much longer for the coral to move," he noted.

"So that coral is going to be deeper than it is today, meaning that less sunlight will penetrate the water.

"And because corals rely a lot on photosynthesis, they therefore have a reduced nutrient intake. This can put the coral under stress."

Just like with the sea walls, Singapore is exploring hybrid solutions - combining the natural with the man-made - to beef up Singapore's natural defences.

Mangroves have on occasion naturally integrated with rock revetment - protective walls - at Kranji Coastal Nature Park, and this contribution to coastal protection remains largely unexplored, said NUS' Prof Koh.

The Coastal Protection and Flood Resilience Institute is running projects to investigate this further, and will develop guidelines for practical implementation, added Prof Koh, who is research director there.

The institute is exploring the design of specialised planters for mangrove seedlings. Researchers will then test the efficacy of the design in terms of wave attenuation and sediment erosion control.

Dr Chua suggested looking at something even more basic - the quality and quantity of sediment.

He is the lead author of a study that found Singapore’s coastlines were historically more resilient against sea-level rise than previously thought.

Published in September, the research looked at how coastlines behaved thousands of years ago. While most global coastlines retreated due to high rates of sea level rise, Singapore's did not.

"At that point, about 7,000 to 8,000 years ago ... there (was) enough sediment being replenished on the coastline to keep up with sea level," said Dr Chua.

"And as sea level rise became stable at about 4mm to 5mm per year ... our coastlines actually advanced, almost like a natural land reclamation project at the time. It went seawards."

With this understanding, scientists can form a better idea of how Singapore's coastlines may respond in future.

Each coast will have to be studied for their differing sediment conditions, said Dr Chua. The northern coast, for example, could prove more resilient due to its muddy nature and "cohesive" sediments which could dissipate wave energy hitting the coastline.

LOOKING INWARDS

While coastlines may be most at risk when sea levels rise, Singapore's interior - and heartlands - are not immune either.

"Inland areas are connected by a network of canals and draining systems. The occurrence of the rise in sea level ... would cause possible overflooding of these irrigation systems due to water not being discharged on time," said SIT's Dr Tay.

This leads to flash flooding during thunderstorms, as was the case in the Orchard and Bukit Timah areas in past years.

Saltwater intrusion can also compromise the quality of freshwater sources from reservoirs, and accelerate the deterioration of underground structures and foundations, leading to increased maintenance costs, potential damage and disruption, said NUS' Prof Koh.

The key lies in better drainage systems, said experts.

Dr Tay pointed to Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, which uses a combination of plants, rocks and civil engineering techniques to prevent flooding and soil erosion; and to adapt to fluctuating water levels by draining.

Besides drain and canal widening work in Bukit Timah, PUB also constructed the Stamford Detention Tank and Stamford Diversion Canal to mitigate flood risks in the Orchard Road area.

NTU's Dr Chua stressed that Singapore already has a "tremendous" amount of infrastructure guarding against localised flooding.

"In some countries when there is flooding, the water actually floods above the banks and beyond the floodplain and extends out from the river systems. In Singapore, it doesn't happen easily because we have built this network of channels and drains to prevent flooding," he said.

Singapore has ensured that its channels are high, deep, and shaped in a way that enables it to manage a high amount of water flowing out.

PLAYING THE LONG GAME

From the perspective of PUB, coastal protection requires adaptive planning and a mix of long-term and short-term strategies to manage the evolving risks of climate change and sea level rise.

Ms Hiong, from the agency's coastal protection department, referred to possible short-term measures as "no regret" infrastructure, using a climatology term indicating methods that could be implemented even in the face of long-term uncertainties.

"We can take an approach where we still raise our sea walls to make sure that they are high enough for the near-term risk, then we monitor carefully the actual sea level rise trend," she said.

The authorities constantly review infrastructure and assess the need for further enhancements in an incremental manner - an approach that helps manage resources and lessen the risk of overspending, Ms Hiong added.

As climate science and technology improves, uncertainties will hopefully reduce over time.

Faced with the drawn-out task of shoring up its coastlines - essentially protecting its very existence - Singapore is in a good place, experts said.

SMU's Assoc Prof Chow said the country possessed the stability to make long-term decisions which would not lose momentum, in contrast to nations with short-term political cycles and constantly changing governments.

Starting the coastal protection fight early would also save costs in the event of global troubles such as inflation or military conflict, he added.

"My concern is that ... if sea level rise does increase on the higher end of projected long-term forecasts, it then gives us less time and less of a buffer to adapt and respond," said Assoc Prof Chow.

Beyond the government's efforts, educating and preventing complacency among the wider public is also critical.

Singaporeans could become "victims of their own success" and take successful coastal protection for granted, said Assoc Prof Chow, pointing to generations spared from the serious floods that occurred in the 50s, 60s, and 70s.

"I'm sorry, but global warming changes the game, literally. My fear in this case is that because it's a long-term issue, you don't see the visible impacts of sea level rise until it's too late," he added.

"It's a very creeping, slow-creeping effect ... People might actually minimise the sort of effect that it has."