‘Worst policy ever’: Retirement time bomb after Malaysia’s pension drawdowns amid pandemic?

Malaysians took RM145 billion out of their pension fund to cushion the impact of the pandemic. More than half aged below 55 ended up with less than RM10,000 in their accounts. Is Malaysia facing a retirement crisis, the programme Insight asks.

During the pandemic, some Malaysians emptied almost all their Employees Provident Fund savings that ordinarily could not be withdrawn before age 55.

This audio is AI-generated.

KUALA LUMPUR: Norazlan Ismail can usually be found behind the wheel of his taxi. But in March, the 49-year-old set off on foot for the National Palace in Kuala Lumpur, from his home town in Johor.

He walked 312 kilometres in six days to deliver a message to the King: to tell Malaysian lawmakers to hear the cries of people like him, in need of financial help.

The father of five wanted the government to release monies from the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), Malaysia’s compulsory savings scheme. With an income of around RM80 (S$23) a day, he found it tough to support his family.

He had more than RM57,000 in his EPF account and hoped for a “last” round of withdrawals, after workers had previously been given dispensation to dip into their accounts to cushion the impact of the pandemic.

But other than a few blisters, he has gained little in the months since his journey and still cannot afford much on his income from driving.

“I’m just scraping by,” he recently told the programme Insight. “I need (money for) my daily expenditure, my children’s education. I also need to repay my loans. … Sometimes I don’t even have money to buy milk.

“My marriage has collapsed because of it, and I need the money (in the EPF) to rebuild my marriage.”

For many others, however, their EPF well is running dry. Between 2020 and last year, through four rounds of COVID-19 withdrawals, 8.1 million Malaysians took RM145 billion out of the pension fund.

As early as February 2021, the EPF reported that about 30 per cent of members had emptied almost all their retirement savings in Account 1, which ordinarily cannot be withdrawn before age 55.

By the end of last year, 51.5 per cent of members under the age of 55 — nearly 6.7 million people — had less than RM10,000 in their accounts.

Based on the EPF’s calculations last year, only about 4 per cent of Malaysians could afford to retire. “It’s a reality today, to be honest,” said EPF chief strategy officer Nurhisham Hussein.

“Some of our members do fall into poverty at retirement or even before retirement because they don’t have the capacity to continue generating the kind of income they need.”

Despite this state of affairs, calls for a further EPF withdrawal have grown louder, by not only Norazlan but also opposition coalition Perikatan Nasional, as inflation pushes up the cost of living.

After having vetoed this all year, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim proposed in the Budget two weeks ago a new EPF account that workers will be able to access flexibly during emergencies.

As the details are worked out, and with the pandemic in the rear-view mirror, some questions also continue to be raised.

Did the previous administrations make the right move in unlocking the EPF? Or is Malaysia facing a retirement time bomb? Is it a crisis that can be defused? What would happen if the pension funds cannot be replenished?

WATCH: Very few Malaysians can afford to retire. What went wrong? (45:35)

OPPORTUNITY COST INVOLVED TOO

For those who drew down on their EPF accounts during the pandemic, it is not just a case of depleted funds now. There has been an opportunity cost: The interest their accounts would have paid from EPF investment earnings.

Since 2011, the average return for EPF members has been 6 per cent a year.

“For members who have money in their accounts, it’s one of the best investments that you can make. For members who don’t have any money in their accounts, it’s not working for them,” said Malaysia University of Science and Technology economist Geoffrey Williams.

By making early withdrawals from the EPF, the poor have become poorer.

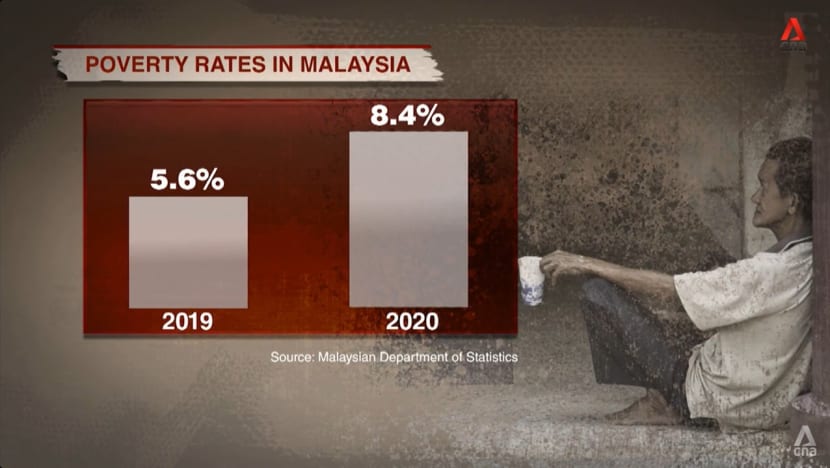

There were, however, extenuating circumstances: The economy contracted, many small and medium enterprises shut down, and 580,000 middle-income households effectively fell into the B40 category, the bottom 40 per cent of the population. The poverty rate also spiked in 2020.

“Critical times require critical action. I don’t disagree with whatever decision that had been made by (then PMs) Muhyiddin (Yassin) and Ismail Sabri,” said Lee Chean Chung, the communications director of Parti Keadilan Rakyat, which was in the opposition then.

But others including Williams look on the decision as a “disastrous move”.

“It’s not the government’s money in the EPF, it’s people’s own money. So they had to use their own money to look after themselves during the lockdowns because the government wasn’t giving them sufficient direct cash transfers,” he said.

Institute of Malaysian and International Studies research fellow Muhammed Abdul Khalid did not mince his words. “(It) is the worst policy ever (that) the country has announced and implemented,” he said. “It’s irresponsible.”

The government did allocate RM530 billion for eight stimulus and aid packages in 2020 and 2021. But as the pandemic wore on, government resources ran low.

“Given the depleted resources that the country had during that time to assist the needy people, maybe this was one of the options — to tap (into) EPF savings — to alleviate their situation,” said Lee.

“I don’t think the government would’ve been able raise enough money at a reasonable rate. So that’s why they made the decision — use your own money to save yourself.”

The EPF is not running out of money, however. Its overall balance sheet remains healthy: Its asset size stood at RM925 billion at the end of 2019, and it ended last year with total investment assets of above RM1 trillion.

“It wasn’t a financial problem for the EPF itself. The impact was more (on) the savings for our members, … especially for those in the lower rungs,” said Nurhisham.

SAVING IS PROVING DIFFICULT

What the pandemic has exposed is a larger issue: Malaysians were just not saving enough. The basic savings target for retirement set by the EPF is RM240,000.

Peter Yong, financial planner turned YouTuber — who co-founded financial education channel Mr Money TV — thinks that figure should be at least RM300,000 to RM350,000, “if you’re looking at the 20 years after retirement and a very thrifty retirement lifestyle”.

But many Malaysians are nowhere close to these numbers. Just over half of EPF members aged 50 to 54 have less than RM50,000 in EPF savings. This translates into less than RM208 a month during retirement, spread over 20 years.

Only “a little over half” of members contribute regularly to the EPF. “The other half don’t,” said Nurhisham. “You might contribute for three or four or five years, then you switch jobs, to something that doesn’t require you to contribute.

And then you miss quite a considerable chunk of your income that could’ve been saved.”

EPF contributions — ordinarily, 11 per cent of monthly salary, with employers contributing another 12 to 13 per cent — are applicable to civil servants and formal employees in the private sector. Gig workers and freelancers are exempt, though they can make voluntary contributions.

And for many, it is a bit of a challenge making ends meet, let alone planning for retirement, via EPF contributions or otherwise.

According to survey results announced this week by financial comparison website RinggitPlus, 71 per cent of respondents save less than RM500 a month, and 55 per cent live from pay cheque to pay cheque.

Making up for the EPF withdrawals by saving more is proving difficult.

“Income isn’t growing as fast as it should’ve been, compared to the cost of living,” said Hafidzi Razali, a director at strategic advisory firm BowerGroupAsia. “We’re talking about a median salary of just RM2,600 (for formal employees). That’s very low.”

While Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 8.7 per cent last year, and there are signs of recovery everywhere, “the growth is not yet inclusive”, said Muhammed, who was economic adviser to former PM Mahathir Mohamad from 2018 to 2020.

“It’s not yet translated (into) the well-being of the people,” he said. “The share of wages (in) GDP — we call it compensation of employees — remains low.”

Compensation of employees last year was 32.4 per cent of GDP in Malaysia and 36.6 per cent in Singapore. In high-tax countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, the figure is more than half of GDP.

The problem in Malaysia is systemic, thinks Yong. “The government, over the years, failed to increase the living standards of Malaysians in terms of bringing in higher-value industries (and) jobs,” he said.

“We may be involved with big companies, big brands, but low-skilled, low-cost (labour). And (for) the ones who are highly skilled, generally a portion of them will move to Singapore.”

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

The government is now exploring ways to boost income. The minimum monthly wage was raised to RM1,500 in May last year, and for micro enterprises, it came into force this July.

The government is also exploring a progressive wage model, and plans will be unveiled in future. “If done properly, this could be something (like what) is implemented in Singapore, where the wages are progressively increased,” cited Hafidzi.

But this, along with some other policies, will not bear fruit anytime soon.

“We can’t just say, ‘Let’s increase the wages of construction workers to RM3,000 tomorrow.’ The industry will collapse,” said Lee, who cited other economic restructuring being done to help workers.

“The government, through the energy transition road map, through our national investment policy master plan, is trying to revive the economy, so that we can all move to a higher value-added economy. … But that’ll take some time.”

It is becoming a race against time to rebuild Malaysia’s retirement kitty owing to the country’s changing demographics.

“We’ll be going from ageing to aged to super-aged within a short span of 50 years,” said Nurhisham. “People like to say ‘ticking time bomb’, right? We’re seeing some of that happening today.”

The EPF started in 1951, when Malaysia’s life expectancy was nearly 54 years. The savings withdrawal age has remained unchanged, but the life expectancy now is 75 years.

“You live longer without money,” said Muhammed, who added that Malays will be the most affected by “old-age poverty”.

According to EPF data as at May, the median EPF savings was RM47,385 among Chinese members, RM15,985 among Indian members and RM7,078 among Malay members, whose savings fell by the biggest proportion among the three ethnic groups following the pandemic.

“It’s not healthy for a multiracial country,” said Muhammed. “(Old-age poverty) is going to get much worse. … The amount (of social assistance) that the government has to give is going to be much increased.”

Some people have suggested higher EPF contribution rates. The latest Budget, meanwhile, included measures such as encouraging voluntary contributions and enhancing incentives for housewives.

In March, Anwar had also put forward a proposal on the use of retirement money as collateral to secure bank loans in emergencies. But this has come under fire from several quarters such as the opposition.

Malaysia’s household debt to GDP ratio is the second highest in the region after Thailand, pointed out Muhammed. “You want them to go and borrow some more? What’s the reason?”

Raising the current retirement age of 60 years and increasing employment among the elderly can be other policy mechanisms to boost savings, suggested Nurhisham.

But increasing the retirement age has its limitations. Those in their 40s and older would still have “little time left to work” to save at least RM600,000 for a “decent” retirement in Kuala Lumpur — a threshold calculated last year by the EPF — cited Williams.

WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

If large numbers of Malaysians retire without sufficient savings, the burden will also fall on the next generation and create a sandwich class.

“The family system has started to break down because people are having (fewer) and (fewer) children,” warned Nurhisham. “So we’re starting to see that first wave of people who are having trouble in retirement really coming through.”

There appears to be no quick fix or magic bullet that will solve the problem and turbocharge retirement savings. Nonetheless, he sees a window of opportunity for “reform” within the next 10 to 20 years.

He added: “In terms of educating the public on the need for saving for retirement, … we have a receptive audience. People do realise the importance of it. It’s just whether they have the capacity for it.”

Take, for example, 30-year-old Sukhvinder Singh, who delivers parcels to offices and residences in Kuala Lumpur.

He earns up to RM5,000 a month, which is enough to support himself and his elderly parents — in contrast to the days of COVID-19 restrictions.

He never made any EPF contributions before because of a lack of money, he said. But he has started to put money into his account voluntarily. His target: 30 per cent of income, although it has been a struggle.

“Things are getting more expensive,” he said. “It’s difficult because I have to support my family. … (My parents) are the ones who brought me up, so what they want I give them. What I can’t give they’ll understand.”

He is “not sure” what he can afford in future, but the EPF will remain important to him. “If I have money — more money — I’ll put (it) in the account,” he said. “Just let my money grow there.”

While Norazlan, on the other hand, wishes that his EPF money was not locked up, poor financial planning was a reason why he did not have much money squirrelled away prior to the pandemic.

Before he was a taxi driver, he worked as a chauffeur and bodyguard, bringing home RM8,000 per month. “I thought the good times would go on indefinitely,” he said. “That’s truly my mistake.

“Whatever happens, I’ll still work hard to raise my children. … Meeting my daily expenditure will, of course, be very hard (work). But that’s my responsibility.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.